9 Ways To Use Artist Statements

Let’s face it; no matter how much you decry, defame, or devalue writing an artist statement, you need it. I guarantee that somewhere along your creative-journey you will be asked for one.

Hopefully, you will outsmart the nay-sayers and not get caught in the same predicament as a painter who contacted me ten months after a prestigious New York gallery had accepted his work. He was a hard worker and a fine artist, and this was a pivotal point in his career. Yet, he had not shown a single piece of work in all ten months. Why?

The gallery asked him for an artist statement and he froze. He’s still painting, still producing canvass after canvass, but as far as I know, he hasn’t written the statement that will, literally, launch his career.

Savvy galleries understand the value of artist statements — that’s why they insist on them. Besides benefiting the artist, an artist statement saves a gallery owner precious time, even as it gives that extra emotional connection that can influence the perception of an artist’s collectability.

Something all creative entrepreneurs can use, yes?

Imagine, three measly paragraphs that can hold you hostage, or set you free.

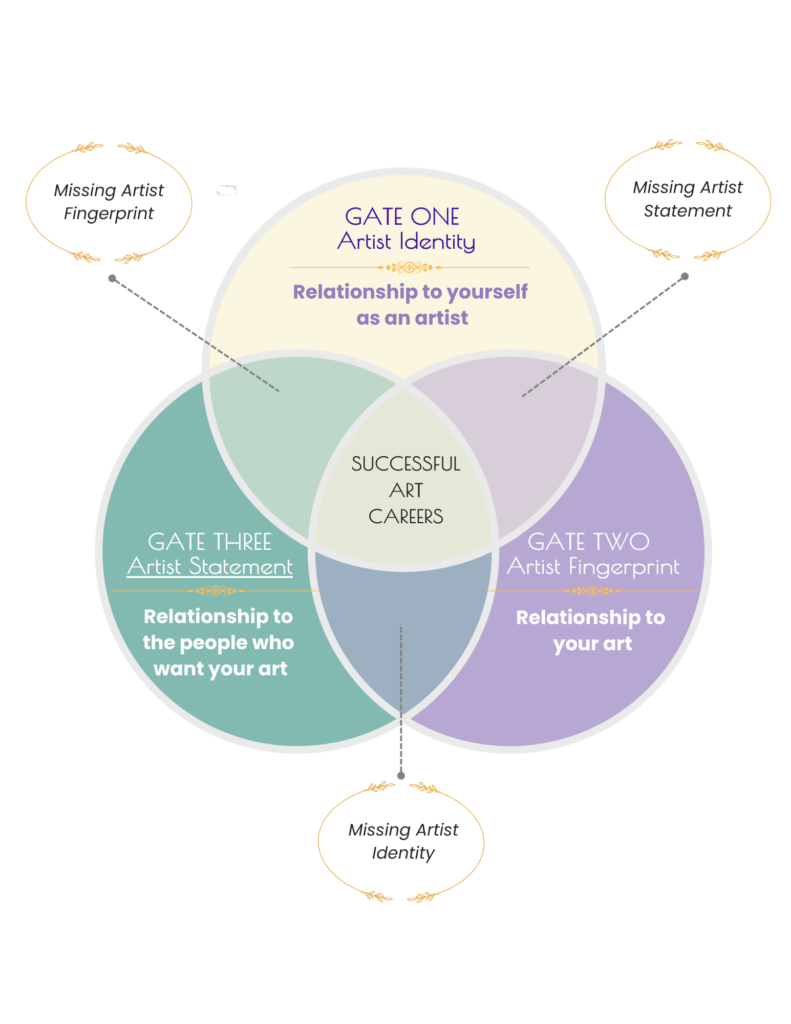

But here’s the kicker: even if your creative entrepreneurship—as a visual artist, sculptor, a writer, dancer, musician, or a creative scientist/engineer/carpenter—doesn’t include galleries, you can steal their ideas and apply what they do to your artist statement.

Here are 9 ways galleries use selected sections, or an entire artists statement:

- In their press releases

- For announcing shows, or the addition of a new artist to their stable

- On their websites

- In the gallery’s portfolio/exhibition book

- To give to writers or journalists for articles

- As historical notes for a retrospective exhibition

- In conversations with collectors and patrons

- As support material on the wall, or beside the artwork

- To hand out at shows for take-home information on a specific artist

A good artist statement gives off the glow of professional detail that makes any gallery owner’s life a bit easier. It also adds spit and polish to the overall effect of the artist-as-person, which in turn compliments the artist-as-artist and the artist-as-investment.

When you give a gallery your artist statement, up front, they credit you with being an organized, professional, and ambitious artist. If a portfolio is missing a statement upon acceptance, most galleries will ask for one.

As with all smart, marketing strategies, a rule of thumb is: know your audience. Each gallery owner has a different idea of what an artist statement is; where, or if, they will use one; and what distinguishes a fine statement from the mediocre.

Before you submit anything, call or write the gallery for their portfolio guidelines. What do they expect to see in your portfolio, and how do they want it presented? If a gallery doesn’t mention the artist statement, ask if they use them and if they have guidelines or suggestions. Many galleries are informal and will simply talk you through their expectations. Be prepared to take notes before you call. I recommend a simple, spiral notebook where you can collect all of your information from every gallery in one place.

When you call, be sure to ask if it is a convenient time for them to answer your questions. You’d be surprised how far a little courtesy like this will go.

Remember, your professional credibility is on the line the minute you open your mouth or send in your portfolio. Here are some suggestions to keep you from making 7 blunders that will cost you dearly:

- Don’t use your artist statement to make up for work that doesn’t work. Get professional feedback before you send anything out.

- Have at least three people, whom you respect, look over your writing for typos, grammatical errors, unclear phrasing, etc.

- Stay away from evaluative comments about your work. Critics’ shoes do not fit artists’ feet.

- Use language that is lively, clear, and accessible. Esoteric, arcane language will not impress anybody.

- Beware of grandiose statements. Low self-esteem loves to dress up in loud outfits.

- Write with details, the spice of life. Generalities generally are flavorless.

- Keep it short (max: three paragraphs).

A gallery is one of your vital links to collectors. When galleries ask for an artist statement, they know what they are doing. Offering their audience more ways to connect with you increases the overall appreciation for what you do, and the perceived value of your work. Of course, if your statement isn’t well written the opposite will be true.

Before you start writing, I suggest a “gathering” stage. This is especially important for the artists who fear that they have nothing to say about their work. I assure you; you do. You have a specific art language, which you use all the time when thinking or talking about your work. The trick is to learn how to catch yourself in the act. Begin with the stated intent that you will listen to yourself. Then follow these tips

- Carry around a spiral notebook or tape recorder for phrases about your work that come in:

- A conversation

- A daydream or night dream

- In the car, in the studio, in the shower, anywhere inspiration strikes

(I don’t know about you, but the more years I tuck under my belt, the clearer I am that my mind lies a lot about what it will remember.)

- Include reflective comments in your technical notebook. What were you thinking as you applied that final glaze, did a color study, selected the perfect marble, composed your latest song, or wrapped fabric samples around your model? Also, take note of which technical notes could make good copy.

- Enlist a friend who is willing to talk with you about what you do and why — someone willing to take notes, or tape-record the conversation. Often we say the perfect thing to someone else

- Let the experts do it for you: Pluck out quotes, of yours, that appeared in articles about your work. Or, if you are clear that you just don’t want to write about yourself, hire a professional writing consultant who specializes in working with artists. They can save you time and heart ache.

For the most part, gallery owners welcome artist statements with open arms. But every once in a while, you may come across a gallery that won’t. Some of these gallery owners/managers are also artists, who instinctively respond more to visual language than to the written word. They assume that the people coming into their galleries do the same thing. It is a common human error to think that everyone is just like us.

Another possibility is for a gallery to have a policy not to use artist statements. Perhaps the gallery likes to create a personal rapport through face-to-face meetings, conveying the sentiments of an artist statement, in person, to their collectors.

In either case, I suggest educating in a gentle, respectful way. Suggest that, since you have already “developed” a statement, you will include it for their “review.” If they “choose” not to use it, that’s fine. Then — and here’s the secret for having galleries end up loving you — when you send in your portfolio, include a TIP SHEET OF POSSIBLE USES clipped to your artist statement. (Just cut & paste the list at the beginning of this special report on how galleries use an artist statement. Be sure to put it on your letterhead. You do have a letterhead, don’t you?)

After you’ve been accepted, respectfully request that the gallery make your statement available for the public. Most galleries, no matter what their personal preferences, are not likely to turn down professionally developed, intelligent, and accessible secondary materials.

Want to take your artist statement to the next level?

Check out Writing The Artist Statement: Revealing the True Spirit of Your Work for a step-by-step guide to your best artist statement ever!